Serpent

This striking and unusual bass instrument first appeared in France in 1590. Its primary purpose was to accompany male voices in plainsong chanting in churches.

Crafted from wood, and bound with leather, the sound can be both subtle and focused, and more formidable when required.

Its cupped mouthpiece, made from wood, horn, or brass, is similar to a brass instrument, but the conical shape and finger-holes are more akin to that of a woodwind instrument such as the recorder or flute, and the cornetto family, of which it was considered a bass instrument in its early days.

By the early 18th century the serpent’s use had expanded to appearances in military bands, both on display and on the field in action.

The serpent would have been heard at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens in the late 18th/early 19th century as background music provided by civic wind bands, and as part of the Duke of York’s Band. It was also featured in military bands in between the acts of theatre productions, and in concert intervals. In time, composers such as Haydn, Beethoven, Berlioz, and Mendelssohn included the serpent in their compositions for mainstream ensembles, such as Harmoniemusik wind bands, and symphony orchestras, utilising it to reinforce bass lines. In addition, more soloistic tenor roles showcased this mysterious instrument’s capabilities.

The instrument was know as the ‘Serpent’ in France, ‘Serpentōn’ in Spain, ‘Serpent’ or ‘Schlangenrohr’ (‘snake-tube’) in Germany, ‘Serpentone’ in Italy, and in the North of England: the ‘Black Pudding’!

Picture: Serpent c.1810, France.[1]Purchase, Robert Alonzo Lehman Bequest, 2005, Metropolitan Museum of Art

London’s Premiere Serpent Players the 18th & 19th Centuries

Rudolph Christopher Sickel

Sickel was the first ever serpent player in the British Army. He’s listed as having performed at Windsor Castle in 1789 with the Duke of York’s Band.[2]John Gleeson ‘Pomp and Circumstance – The Band of the Coldstream Guards, A History 1685 – 2017‘. p.411

Is he perhaps the same man as A. Sichel (fl.1794-1799), who was a serpent player and double bassist in the Second Regiment of Guards? Sichel also performed in the oratorios at the Drury Lane Theatre, and in the Handel Concerts in Westminster Abbey.

In 1799 an “A. Sickle”, performer at the King’s Theatre, signed a petition, imploring the Lord Chamberlain to stop manager William Taylor’s licence until he paid the musicians’ salaries.[3]Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. … Continue reading

He lived at No.39 Orchard Street, Westminster.

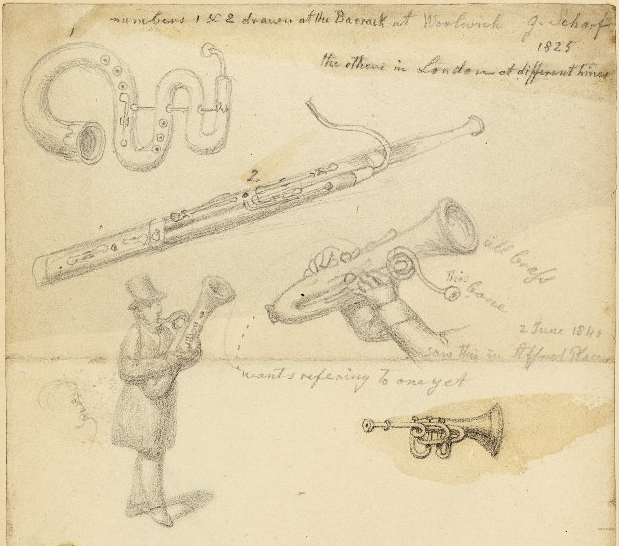

Picture: Anonymous English Military serpent with 5 keys c.1800[4]Picture Credit: © Original print from 1809 used with permission of Andy Kershaw

Mr Hurworth (fl. 1790s)

Hurworth was a serpent player from Richmond, North Yorkshire who held a post in the Private Band of King George III. It is said that his playing was so virtuosic that he practised flute studies.

Mr Hurst (fl. 1794)

Hurst was a member of the First Regiment of Guards. He also performed on the serpent in the Oxford Meeting of 1793, and the Handel concerts in Westminster Abbey.[5]Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. … Continue reading

The Duke of Gloucester’s Band, an ensemble associated with the Third Regiment of the Scots Guards, includes a serpent, is pictured here.[6]Unknown author, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Louis Alexandre Frichot

Frichot (1760-1825) was a renowned French serpent player and inventor who lived in London, having fled from France during the Revolution in the early 1790’s. He performed in London, including with the Society of Ancient Music.

In 1825, the Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review noted:

“About thirty years ago there came to England a Frenchman, of the name of Frichot, who played an air with variations, of rapid execution, and containing very difficult chromatic passages. His instrument was a long tube terminated by a globe about 7 or 8 inches in diameter. . . . It was in serpentine form, but the bends were not more than a foot in extent.”[7]Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. … Continue reading

The instrument described is an early version of the bass horn, which was built for him by George Astor in London in the late 18th century.

After the Peace of Amiens, Frichot returned to France. He taught music and invented the basse-trompette, patented in 1810.

Picture: A print published by Aaron Martinet in his 1811 series, Troupes Françaises, shows a French military serpent player[8]One of 296 prints in the collection, the image is titled “Garde Impériale: Musicien des Grenadiers a pied“. Public Domain via Will Kimball’s website

Joseph Wilmshurst (fl. 1794-1823)

Serpent player, kettledrummer, and singer Wilmshurst performed at the Oxford Meeting in 1793, and in the Handel concerts at Westminster Abbey. He is likely to be the same “Wilmhurst” who performed at the Drury Lane Theatre from 1802-1814

He lived at Green’s Court, Tothill Fields, London.[9]Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. … Continue reading

J. L. Clarke (fl. 1784-1811)

Described as a player of “bass” (most likely a bass horn or upright serpent) in Doane’s Musical Dictionary of 1794, Clarke performed in the Handelian celebrations in Westminster Abbey, and in the Concerts of Ancient Music, and Covent Garden Oratorios.

In 1794 he lived in Bow Street, Westminster. [10]Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. … Continue reading

Quotes about the Serpent:

Charles Burney (1726-1814) describes the role of the early serpent:

“In the French churches, there is an instrument on each side of the choir, called the Serpent, from its shape, I suppose, for it undulates like one. This gives the tone in chanting, and plays the bass when they sing in parts. It mixes with them better than the organ, (and) is less likely to overpower or destroy by bad temperament, that perfect tone of which only the voice is capable. The Serpent keeps the voices up to their pitch, and so is a kind of crutch for them to lean on.”

And on another occasion:

“The Serpent is not only overblown and detestably out of tune, but exactly resembling in tone that of a great hungry, or rather angry Essex calf.”

Georg F. Handel (1685-1759), on hearing the Serpent for the first time:

“Aye, but not the Serpent that seduced Eve.”

Michael Praetorius (1571-1621)

“Most unlovely and bullocky.”

Canon Edme Guillaume (supposed inventor of the serpent in 1590)

“The instrument gave a fresh zest to Gregorian Plainsong.”

Abbe Beaugeois, in 1827, referencing the need for good technique when pitching the notes:

“The (Serpent) student needs a good ear, because many of the notes are only given by the lips.”

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Bibliography & Credits

Researchers – Laura Piras & Adrian France

References

| ↑1 | Purchase, Robert Alonzo Lehman Bequest, 2005, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Gleeson ‘Pomp and Circumstance – The Band of the Coldstream Guards, A History 1685 – 2017‘. p.411 |

| ↑3 | Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. South Illinois University Press, 1975. Volume 13, p.385 |

| ↑4 | Picture Credit: © Original print from 1809 used with permission of Andy Kershaw |

| ↑5 | Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. South Illinois University Press, 1975. Volume 8, p.57 |

| ↑6 | Unknown author, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

| ↑7 | Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. South Illinois University Press, 1975. Volume 5, p.413 |

| ↑8 | One of 296 prints in the collection, the image is titled “Garde Impériale: Musicien des Grenadiers a pied“. Public Domain via Will Kimball’s website |

| ↑9 | Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. South Illinois University Press, 1975. Volume 16 p.160 |

| ↑10 | Highfill, Philip H., JR, Burnim, Kalman A., Langhans, Edward A. – A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, & Other Stage Personnel in London 1660-1800. South Illinois University Press, 1975. Volume 3, p.302 |